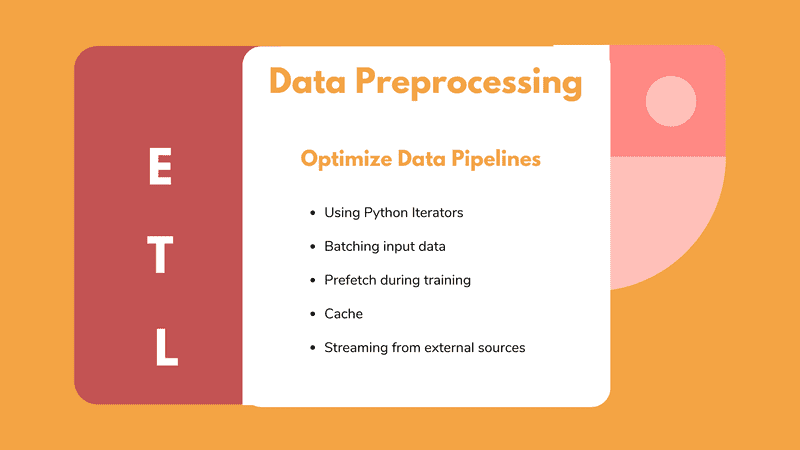

Data preprocessing is an integral part of building machine learning applications. However, most machine learning engineers don’t spend the appropriate amount of time on it because sometimes it can be hard and tedious. When it comes to deep learning especially, the amount of data we have to manipulate, makes it even more difficult to do so. And of course, is not just enough to build a data pipeline, we also have to make it as efficient and as fast as possible.

As we saw in our previous article, data pipelines follow the ETL paradigm. ETL is an acronym and stands for extraction, transformation, loading. Last time we explore the first two parts (E, T) and saw how to use TensorFlow to extract data from multiple data sources and transform them into our desired format. We also talked about functional programming and how it can be very handy when building input pipelines because we can specify all of our transformations in the form of a chain.

This time, we are going to discuss the last part of the pipeline called loading. Loading essentially means the feeding of our data into the deep learning model for training or inference. But we’re going to take it a step further as we will also focus on how to make the pipeline high performant in terms of speed and hardware utilization, using techniques such as batching, prefetching, and caching.

So without further ado, let’s get started with loading. But before that, let me remind you of our initial problem throughout this article series. Tl;dr: we’re trying to convert a Jupyter notebook that performs semantic segmentation on images into production-ready code and deploy it in the cloud. As far as the data we’re using concerns, they are a collection of pet images borrowed by the Oxford University. Note that you can find our whole codebase so far in our GitHub repository.

OK let’s do it.

Loading

Loading essentially refers to passing the data into our model for training. In terms of the code is as simple as writing:

self.model.fit(self.train_dataset, epochs=self.epoches, steps_per_epoch=self.steps_per_epoch, validation_steps=self.validation_steps, validation_data=self.test_dataset)

All we did here, was calling the “fit()” function of the Keras API, defining the number of epochs, the number of steps per epoch, the validation steps and simply pass the data as an argument. Is that enough? Can I call off the article now? If only it was that easy.

Actually, let me remind us of our current pipeline until now.

self.dataset, self.info = DataLoader().load_data(self.config.data)

train = self.dataset['train'].map(lambda image: DataLoader._preprocess_train(image,image_size), num_parallel_calls=tf.data.experimental.AUTOTUNE)

train_dataset = train.shuffle(buffer_size)

As you can see and you might even remember from the last article, we are loading our data using the TensorFlow dataset library, we then use the “map()” function to apply some sort of preprocessing into each data point, and then we shuffle them. The preprocessing function resizes each data point, flips it, and normalizes the image. So you might think that, since the images are extracted from the data source and transformed into the right format, we can just go ahead and pass them into the fit() function. In theory yeah this is correct. But we also need to take care of some other things.

Sometimes we don’t just want to pass the data into our function as we may care about having more explicit control of the training loop. To do that who may need to iterate over the data so we can properly construct the training loop as we’d like.

Tip:Running a for-loop in a dataset is almost always a bad idea because it will load the entire dataset into memory. Instead, we want to use Python’s iterators.

Iterators

An iterator is nothing more than an object that enables us to traverse throughout our collection, usually a list. In our case, that collection is a data set. The big advantage of iterators is lazy loading. Instead of loading the entire dataset into memory, the iterator loads each data point only when it’s needed. Needless to say that this is what tf.data is using behind the scenes. But we can also do that manually.

In tf.data code we can have something like this:

dataset = tf.data.Dataset.range(2)

for element in dataset:

train(element)

Or we can simply get the iterator using the “iter” function and then loop over it using the “get_next” function

iterator = iter(dataset)

train(iterator.get_next())

Or we can use Python’s built-in “iter” function:

iterator = iter(dataset)

train(next(iterator))

We can also get an numpy iterator from a Tensorflow Dataset object:

for element in dataset.as_numpy_iterator():

train(element)

We have many options, that’s for sure. We also do care about performance.

Ok, I keep saying performance and performance, but I haven’t really explained what does that means. Performance in terms of what? And how can we measure performance? If I had to put it in a few words, I would say that performance is how fast the whole pipeline from extraction to loading is executed. If I wanted to dive a little deeper, I would say that performance is latency, throughput, ease of implementation, maintenance, and hardware utilization.

You see the thing is that data for deep learning is big. I mean really huge. And sometimes we aren’t able to load all of them into memory or each processing step might take far too long and the model will have to wait until it’s completed. Or we simply don’t have enough resources to manipulate all of them.

In the previous article, we discussed a well-known trick to address some of the issues, called parallel processing where we run the operation simultaneously into our different CPU cores. Today we will mainly focus on some other techniques. The first one is called batching.

Batching

Batch processing has a slightly different meaning for a software engineer and a machine learning engineer. The former thinks batching as a method to run high volume, repetitive jobs into groups with no human interaction while the latter thinks of it as the partitioning of data into chunks.

While in classical software engineering, batching help us avoid having computer resources idle and run the jobs when the resources are available, in machine learning batches make the training much more efficient because of the way the stochastic gradient descent algorithm works.

I’m not gonna go deep into many details but in essence, instead of updating the weights after training every single data point, we update the weights after every batch. This modification of the algorithm is called by many Batch Gradient Descent (for more details check out the link at the end).

In tensorflow and tf.data, creating batches is as easy as this:

train = train.batch(batch_size)

That way after loading and manipulating our data we can split them into small chunks so we can pass them into the model for training. Not only do we train our model using batch gradient descent but also we apply all of our transformations on one batch at a time, avoiding to load all our data into memory at once. Please note that the batch size refers to the number of elements in each batch.

Now pay attention to this: we load a batch, we preprocess it and then we feed it into the model for training in sequential order. Does not mean that while the model is running, the whole pipeline remains idle waiting for the training to be completed so it can begin processing the next batch? That’s right. Ideally, we would want to do both of these operations at the same time. While the model is training on a batch, we can preprocess the next batch simultaneously.

But can we do that? Of course!

Prefetching

Tensorflow lets us prefetch the data while our model is trained using the prefetching function. Prefetching overlaps the preprocessing and model execution of a training step. While the model is executing training step n, the input pipeline is reading the data for step n+1. That way we can reduce not only the overall processing time but the training time as well.

train= train_train.prefetch(buffer_size=tf.data.experimental.AUTOTUNE)

For those who are more tech-savvy, using prefetching is like having a decoupled producer-consumer system coordinated by a buffer. In our case, the producer is the data processing and the consumer is the model. The buffer is handling the transportation of the data from one to the other. Keep in mind that the buffer size should be equal or less with the number of elements the model is expecting for training.

Caching

Another cool trick that we can utilize to increase our pipeline performance is caching. Caching is a way to temporarily store data in memory or in local storage to avoid repeating stuff like the reading and the extraction. Since each data point will be fed into the model more than once (one time for each epoch), why not store it into the memory? That is exactly we can do using the caching function from tf.data

train_ train = train.cache()

So each transformation is applied before the caching function will be executed and only on the first epoch. The caveat here is that we have to be very careful on the limitations of our resources, to avoid overloading the cache with too much data. However, if we have complex transformations, is usually preferred to do them offline rather than executing them on a training job and cache the results.

At this point, I like to say that this is all you need to know about building data pipelines and make them as efficient as possible. Our whole pipeline is finally in place and it looks like this:

data = tfds.load(data_config.path, with_info=data_config.load_with_info)

train = dataset['train'].map(lambda image: DataLoader._preprocess_train(image, image_size),num_parallel_calls=tf.data.experimental.AUTOTUNE)

train_dataset = train.shuffle(buffer_size).batch(batch_size).cache().repeat()

model.fit(train_dataset)

However, before I let you go I want to discuss another very important topic that you may or may not need in your everyday coding life. Streaming. In fact, with streaming we go back to the extraction phase of our pipeline, but I feel like I need to include that here for completion.

Streaming

So first of all what are we trying to solve here with streaming? And second what is streaming?

There are use cases where we don’t know the full size of our data as they might come from an unbounded source. For example, we can acquire them by an external API or we may extract them from a database of another service that we don’t know many details. Imagine for example that we have an Internet of Things application where we collect data from different sensors and we apply some sort of machine learning to them. In this scenario, we don’t really know the full side of the data and we may say that we have an infinite source that will generate data forever. So how do we handle that and how we can incorporate those data into a data pipeline?

Here is when Streaming comes really handy. But what is streaming?

Streaming is a method of transmitting or receiving data (over a computer network) as a steady, continuous flow, allowing playback to start while the rest of the data is still being received.

What is happening behind the scenes, is that the sender and the receiver open a connection that remains open for as long as they need. Then the sender sends very small chunks of our data through the connection and the receiver gets them and reassembles them into their original form.

Can you now see how useful that can be for us? We can open a connection with an external data source and keep processing the data and training our model on them for as long as they come.

To make our lives easier, there is an open-source library called Tensorflow I/O. Tensorflow I/O supports many different data sources not included in the original TensorFlow code such as BigQuery and Kafka and multiple formats like audio, medical images, and genomic data. And of course, the output is fully compatible with tf.data. So we can apply all the functions and tricks we talked so far in the past two articles.

Let’s see an example of when our data come from Kafka. For those of you who don’t know, Kafka is a high performant, distributed messaging system that is been used widely in the industry.

import tensorflow_io.kafka as kafka_io

dataset = kafka_io.KafkaDataset ('topic', server = "our server", group=" our group")

Dataset = dataset.map(...)

Don’t hang up too much on the Kafka details. The essence is that it makes streaming so simple I want to cry from excitement.

As a side material, I strongly suggest the TensorFlow: Advanced Techniques Specialization course by deeplearning.ai hosted on Coursera, which will give you a foundational understanding on Tensorflow

Conclusion

In the last two articles of the Deep Learning in the production series, we discovered how to build efficient data pipelines in TensorFlow using patterns like ETL and functional programming and explored different techniques and tricks to optimize their performance. So I think at this point we’re ready to say goodbye to data processing and continue with the actual training of our model.

Training may sound simple and maybe you think that there’s not much new stuff to learn here, but I can assure you that it’s not the case. Have you ever train your data on distributed systems? Have you used cloud computing to take advantage of its resources instead of draining your laptop? And what about GPU’s?

These are only some of the topics we will cover later. If that sounds interesting, you are more than welcome to come aboard and join our AI Summer community by subscribing to our newsletter.

See you soon…

References

-

cloud.google.com, Batch processing

-

tensorflow youtube channel, Inside TensorFlow: tf.data + tf.distribute

-

tensorflow youtube channel, tf.data: Fast, flexible, and easy-to-use input pipelines

-

tensorflow youtube channel, Scaling Tensorflow data processing with tf.data

-

tensorflow.org, Better performance with the tf.data API

-

datacamp.com, Python Iterator Tutorial

-

ruder.io, An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms

-

aws.amazon.com, What is Streaming Data?

-

searchstorage.techtarget.com, Cache (computing)

* Disclosure: Please note that some of the links above might be affiliate links, and at no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you decide to make a purchase after clicking through.