A laboratory in Lawrenceville is harnessing the intellectual talent of Pittsburgh’s research institutions to target cancer. We speak with a man on a mission to help cancer patients by using artificial intelligence. It starts with the cryogenically frozen tumor. Predictive Oncology CEO Raymond Vennare doesn’t like the term tumor to refer to the cancer they study.“I refer to them as human beings. These human beings are repurposing their lives for us for a purpose, to be able to find cures to help their descendants; that’s their legacy,” Vennare said. Vennare is not a scientist. He’s a businessman who builds biotech companies. He’s had a bullseye on cancer for 15 years.What’s different about this venture? The mission: to get cancer drugs that work to market, years faster.“And what would have taken three to five years and millions of dollars, we were able to do in a couple of cycles in 11, 12, 13 weeks,” Vennare said.“In pre-trial drug development tumor heterogeneity, patient heterogeneity isn’t introduced early enough,” said Amy Ewing, a senior scientist at Predictive Oncology.Translation: Predictive Oncology’s scientists are focusing on cell biology, molecular biology, computational biology and bioinformatics to determine how cancer drugs work on real human tumor tissue.A bank of invaluable tumor samples allows them to crunch that data faster.Remember, those samples are people.“When I think about cancer, I see their faces,” Vennare said. “I don’t see cells on a computer screen.”Vennare sees his brother, Alfred.“He was my first best friend. I grew up, Al, Alfred was always there. And whenever I needed something, Alfred was always there.”He also thinks of his parents.“In my case, my mother and my father and my brother sequentially died of cancer, which means I was the caregiver. My family was the caregiver, my siblings and my sister were caregivers for five consecutive years,” he said.Ewing thinks of her father.“I lost my father to prostate cancer about a year ago,” she said. “So to me, I have a deeper understanding now of what it means to have another day, or another month, or another year. I think that’s really what gets me up in the morning now is to say that I want to carry on his legacy and help somebody else have more time with their family members.”With a board of scientific advisors that includes an astronaut and some of the top scientists in the country, Vennare says ethics is part of the ongoing artificial intelligence conversation.”The purpose is to make the job of the scientist easier, so they can expedite the process of discovery,” he said. “It’s not AI that’s going to do that, it’s the scientists that are going to do that.”Venarre says Predictive Oncology is agnostic, meaning this company seeks to help drug companies quickly zero in on effective drugs for all kinds of cancer.

A laboratory in Lawrenceville is harnessing the intellectual talent of Pittsburgh’s research institutions to target cancer. We speak with a man on a mission to help cancer patients by using artificial intelligence.

It starts with the cryogenically frozen tumor. Predictive Oncology CEO Raymond Vennare doesn’t like the term tumor to refer to the cancer they study.

“I refer to them as human beings. These human beings are repurposing their lives for us for a purpose, to be able to find cures to help their descendants; that’s their legacy,” Vennare said.

Vennare is not a scientist. He’s a businessman who builds biotech companies. He’s had a bullseye on cancer for 15 years.

What’s different about this venture? The mission: to get cancer drugs that work to market, years faster.

“And what would have taken three to five years and millions of dollars, we were able to do in a couple of cycles in 11, 12, 13 weeks,” Vennare said.

“In pre-trial drug development tumor heterogeneity, patient heterogeneity isn’t introduced early enough,” said Amy Ewing, a senior scientist at Predictive Oncology.

Translation: Predictive Oncology’s scientists are focusing on cell biology, molecular biology, computational biology and bioinformatics to determine how cancer drugs work on real human tumor tissue.

A bank of invaluable tumor samples allows them to crunch that data faster.

Remember, those samples are people.

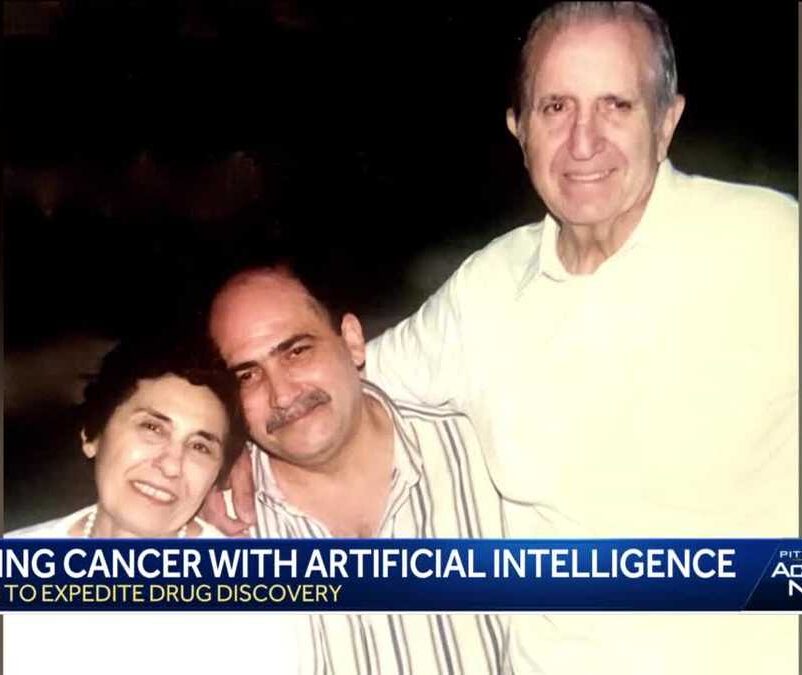

“When I think about cancer, I see their faces,” Vennare said. “I don’t see cells on a computer screen.”

Vennare sees his brother, Alfred.

“He was my first best friend. [When] I grew up, Al, Alfred was always there. And whenever I needed something, Alfred was always there.”

He also thinks of his parents.

“In my case, my mother and my father and my brother sequentially died of cancer, which means I was the caregiver. My family was the caregiver, my siblings and my sister were caregivers for five consecutive years,” he said.

Ewing thinks of her father.

“I lost my father to prostate cancer about a year ago,” she said. “So to me, I have a deeper understanding now of what it means to have another day, or another month, or another year. I think that’s really what gets me up in the morning now is to say that I want to carry on his legacy and help somebody else have more time with their family members.”

With a board of scientific advisors that includes an astronaut and some of the top scientists in the country, Vennare says ethics is part of the ongoing artificial intelligence conversation.

“The purpose is to make the job of the scientist easier, so they can expedite the process of discovery,” he said. “It’s not AI that’s going to do that, it’s the scientists that are going to do that.”

Venarre says Predictive Oncology is agnostic, meaning this company seeks to help drug companies quickly zero in on effective drugs for all kinds of cancer.