The problem with soft skills (or human skills) is that they mean different things for different people – they are not taught at school, so they aren’t defined like ‘proper’ subjects are, and yet many of us think that we are very good at them without any kind of training.

As discussed in last month’s article, the World Bank is undertaking studies to show that soft skills can and should be taught within schools. As the Bank provides advice to both ministries of education and ministries of labor in developing countries, it has the reach to prove (or disprove) the benefits of soft skills in the workplace, as well as in education.

Measuring outcomes

As Samantha De Martino, an economist with the Mind, Behaviour and Development Unit in the Poverty & Equity Global Practice of the World Bank, put it when we spoke: “We know that soft skills matter for education and labor market outcomes. The World Bank has done research in countries such as the Philippines, Indonesia, Georgia, Moldova, India, and Kenya – a lot of different places where employers indicate they need these soft skills. The great news is that soft skills are malleable – they can be learned and improved upon throughout adolescence and even in adulthood.”

However, defining soft skills required by employers is a challenge. Not least, because these skills are difficult to measure – in part due to their intangible nature in work and education. De Martino points out there is also more that could be done to understand the impact of soft skills, and how they interact with different facets of the labor market. The Bank has been working on developing innovative methods to measure soft skills of unemployed youth, including task-based measures delivered via mobile devices, first in South Africa and soon expanding elsewhere. The skills feedback the disadvantaged unemployed youth receive from this data collection helps improve their confidence and signalling to employers, ultimately improving employment outcomes.

Whilst more studies on soft skills at work need to be undertaken, more analysis is also required to determine exactly which human skills are particularly valuable to the workplace – such as personal initiative, reliability, or a growth mindset – and how employers can focus on these skills in particular.

The value of initiative

As Paolo Belli, World Bank Practice Manager for Social Protection and Jobs for Eastern and Southern Africa, puts it: “Helping people to develop a growth mindset is essential, particularly when working with marginalized groups, who have experienced professional setbacks or failure. It is important for these groups to see what success looks like, through internships, apprenticeship programs, or new income generating activities.”

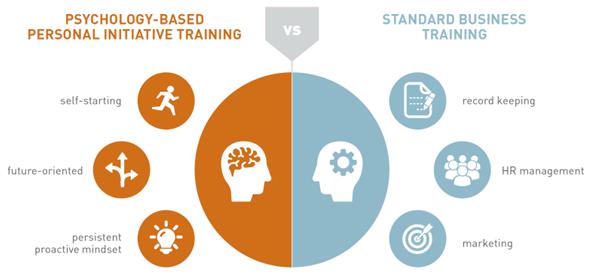

As I am studying for a doctorate on the subject of initiative, I was fascinated by another World Bank study that included a focus on growth mindsets within the context of teaching personal initiative to entrepreneurs. This study (also available in a briefing paper), conducted in Togo, looked at the outcome on company profitability when comparing standard business training with a psychology-based personal initiative training (with a control group who received no training). A group of 1,500 entrepreneurs (split equally between men and women) were put into 3 groups. The personal initiative and standard business training groups were given 36 hours of training, while the control group was given no training at all.

Psychology vs Business Based Training

Those entrepreneurs who went through the personal initiative training saw their company profits increase by 30% and, for those who had undertaken standard business training, profits increased by 5%, over a two-year period, compared to the control group. The effect on profitability was even higher for women entrepreneurs receiving personal initiative training, with profits increasing by 40%.

The value of open data on evaluating soft skills

Much of the Bank’s research is available via its Open Knowledge Repository, but it is also partnering with the likes of Cal Poly to work with students on analysing large volumes of data. For example, De Martino and her colleagues have been advising on a project using AI algorithms to understand which soft skills match together with different industries across countries.

“I think there were quite a few advancements made in terms of cross-sectoral learnings on both sides; the students picked up some psychometrics and econometrics and applied it to real world challenges and we picked up some computer science and AI tools to apply to our data,” says De Martino. “This type of partnership and cross-pollination is really crucial to break down barriers in understanding in our respective fields to make advancements and ultimately improve outcomes for our clients”.

Testing the value of soft skills at scale

The World Bank is unique insofar that it has the resources and reach into national education and labor ministries – which allows it to make a difference at scale. With the acceleration of automation in the workplace, we need to move faster to ensure that employees have meaningful jobs. The good news is that there is a growing consensus on the importance of soft skills. But a continued focus on large scale interventions to evaluate, and where appropriate encourage, soft skills within the labor force by the World Bank could have a meaningful impact on many lives.