This time, we are going to keep ourselves busy with another family of

Reinforcement learning algorithms, called policy-based methods. If you recall,

there are two main groups of techniques when it comes to model-free

Reinforcement Learning.

We analyze the first ones in two previous articles where we talked about

Q-learning and Deep Q Networks and different improvement on the basic models

such as Double Deep Q Networks and Prioritized Replay. Check them out

here and here.

Let’s do a quick rewind. Remember that we frame our problems as Markov

Decision Processes and that our goal is to find the best Policy, which is a

mapping from states to actions. In other words, we want to know what the action

with the maximum expected reward from a given state is. In value-based methods,

we achieve that by finding or approximating the Value function and then extract

the Policy. What if we completely ditch the value part and find directly the

Policy. This is what Policy-based methods do.

Don’t get me wrong. Q-learning and Deep Q networks are great, and they are used

in plenty application, but Policy-based methods offer some different advantages:

-

They converge more easily to a local or global maximum and they don’t suffer

from oscillation -

They are highly effective in high-dimensional or continuous spaces

-

They can learn stochastic policies (Stochastic policies give a

probability distribution over actions and not a deterministic action.

They used in stochastic environments, which they modeled as Partially

Observable Markov Decision Processes where we do not know for sure the

result of each action)

Hold on a minute. I told about convergence, local maximum, continuous space,

stochasticity. What’s going on in here?

Well, the thing is that Policy based reinforcement learning is an optimization

problem. But what does this mean?

We have a policy (π) with some parameters theta (θ) that outputs a probability

distribution over actions. We want to find the best theta that produces the best

policy. But how we evaluate if a policy is good or bad? We use a policy

objective function J(θ), which most often is the expected accumulative reward.

Also, the objective function varies whether we have episodic or continuing

environments.

So here we are, with an optimization problem in our hands. All we have to do is

find the parameters theta (θ) that maximizes J(θ) and we have our optimal

policy.

The first approach is to use a brute force technique and check the whole policy

space. Hmm, not so good.

The second approach is to use a direct search in the policy space or a subset of

it. And here we introduce the term of Policy Search. In fact, there are two

families of algorithms that we can use. Let’s call them:

-

Gradient free

-

Gradient-based

Think of any algorithm you have ever used to solve an optimization task, which

does not use derivatives. That’s a gradient-free method and most of them can be

used in our case. Some examples include:

-

Hill climbing is a random

iterative local search -

Simplex: a popular linear

programming algorithm (if you dig linear algebra check him out) -

Simulated annealing,

which moves across different states based on some probability. -

Evolutionary

algorithms that

simulate the process of physical evolution. They start from a random state

represented as a genome and through crossover, mutation and physical

selection they find the strongest generation (or the maximum value). The

whole “Survival of the fittest” concept wrapped in an algorithm.

The second family of methods uses Gradient

Descent or to be more accurate

Gradient Ascent.

In (vanilla) gradient descent, we:

-

Initialize the parameters theta

-

Generate the next episode

-

Get long-term reward

-

Update theta based on reward for all time steps

-

Repeat

But there is a small issue. Can we compute the gradient theta in an analytical

form? Because if we can’t, the whole process goes to the trash. It turns out

that we can with a little trick. We have to assume that policy is differentiable

whenever it is non-zero and to use logarithms. Moreover we define the

state-action trajectory (τ) as a sequence of states, actions and rewards: τ =

(s0,a0,r0, s1,a1,r1…, st,at,rt).

I think that’s enough math for one day. The result, of course, is that we have

the gradient in an analytical form and we can now apply our algorithm.

The algorithm described so far (with a slight difference) is called

REINFORCE or Monte Carlo policy gradient. The difference from vanilla

policy gradients is that we got rid of expectation in the reward as it is not

very practical. Instead, we use stochastic gradient descent to update the theta.

We sample from the expectation to calculate the reward for the episode and

then update the parameters for each step of the episode. It’s quite a

straightforward algorithm.

Ok, let’s simplify all those things. You can think policy gradients as so:

For every episode that we got a positive reward, the algorithm will increase the

probability of those actions in the future. Similarly, for negative rewards, the

algorithms will decrease the probability of the actions. As a result, in time,

the actions that lead to negative results are slowly going to be filtered out

and those with positive results will become more and more likely. That’s it. If

you want to remember one thing from the whole article, this is it. That’s the

essence of policy gradients. The only thing that changes every time is how we

compute the reward, what policy do we choose (Softmax, Gaussian etc..) and how

do we update the parameters.

Now let’s move on.

REINFORCE is, as mentioned, a stochastic gradient descent algorithm. Taking that

into consideration, a question comes to mind. Why not use Neural Networks to

approximate the policy and update the theta?

Bingo!!

It is time to introduce neural networks into the equation:

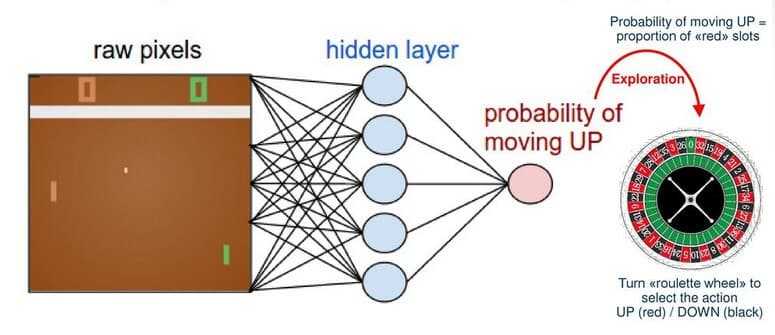

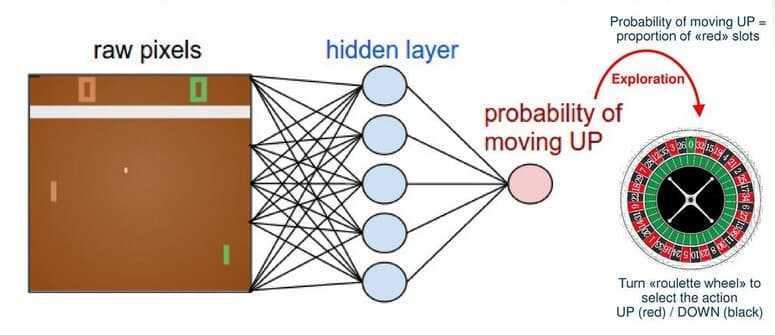

We can, of course, use pretty much any machine learning model to approximate the

policy function (π), but we use a neural network such as a Convolutional Network

because we like Deep Learning. A famous example is an agent that learns to play

the game of Pong using Policy

gradients and Neural Networks. In that example, a network receives as input

frames from the game and outputs a probability of going up or down.

http://karpathy.github.io/2016/05/31/rl/

We will try to do something similar using the gym environment by OpenAI.

class REINFORCEAgent:

def build_model(self):

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(self.hidden1, input_dim=self.state_size, activation='relu', kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform'))

model.add(Dense(self.hidden2, activation='relu', kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform'))

model.add(Dense(self.action_size, activation='softmax', kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform'))

model.compile(loss="categorical_crossentropy", optimizer=Adam(lr=self.learning_rate))

return model

def get_action(self, state):

policy = self.model.predict(state, batch_size=1).flatten()

return np.random.choice(self.action_size, 1, p=policy)[0]

def discount_rewards(self, rewards):

discounted_rewards = np.zeros_like(rewards)

running_add = 0

for t in reversed(range(0, len(rewards))):

running_add = running_add * self.discount_factor + rewards[t]

discounted_rewards[t] = running_add

return discounted_rewards

def train_model(self):

episode_length = len(self.states)

discounted_rewards = self.discount_rewards(self.rewards)

discounted_rewards -= np.mean(discounted_rewards)

discounted_rewards /= np.std(discounted_rewards)

update_inputs = np.zeros((episode_length, self.state_size))

advantages = np.zeros((episode_length, self.action_size))

for i in range(episode_length):

update_inputs[i] = self.states[i]

advantages[i][self.actions[i]] = discounted_rewards[i]

self.model.fit(update_inputs, advantages, epochs=1, verbose=0)

env = gym.make('CartPole-v1')

state_size = env.observation_space.shape[0]

action_size = env.action_space.n

scores, episodes = [], []

agent = REINFORCEAgent(state_size, action_size)

for e in range(EPISODES):

done = False

score = 0

state = env.reset()

state = np.reshape(state, [1, state_size])

while not done:

if agent.render:

env.render()

action = agent.get_action(state)

next_state, reward, done, info = env.step(action)

next_state = np.reshape(next_state, [1, state_size])

reward = reward if not done or score == 499 else -100

agent.append_sample(state, action, reward)

score += reward

state = next_state

if done:

agent.train_model()

score = score if score == 500 else score + 100

scores.append(score)

episodes.append(e)

You can see that the isn’t trivial. We define the neural network model , the monte carlo sampling,

the training process and then we let the agent to learn by interacting with the environment and

update the weight at the end of each episode.

For more material on Policy Gradients, I highly suggest the Advanced AI: Deep Reinforcement Learning Course in Python on Udemy. It covers everything you need to know from Deep Q Learning to Policy Gradients and Actor critics.

But policy gradients have their own drawbacks. The most important is that they have a high variance and it can be notoriously difficult to stabilize the model parameters.

Do you wannna know how we solve this? Keep in touch…

(Hint: its actor critic models)

* Disclosure: Please note that some of the links above might be affiliate links, and at no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you decide to make a purchase after clicking through.