In the past few weeks, much has been written about the uses of artificial intelligence and its potential to take the place not only of factory workers but also of highly specialized professionals, such as lawyers and engineers. Many physicians have concluded that AI will never replace a hand at the bedside. As a former medical school dean and hospital vice president, I disagree. And this isn’t just my opinion. At an international meeting recently in Parma, Italy, attended by health policy experts and physicians, only one — a physician — argued that I was wrong. The tide is changing. How long for AI maturity, or “singularity,” the term now used for when AI surpasses human intelligence? One consensus estimates 25 years. Maybe less.

I believe that AI will perform all three main functions of physicians, the first of which is determining a diagnosis and medical treatment; collecting and analyzing data; and then making recommendations on further testing and treatment. Most of this can be done now. AI in some cases is already performing better than physicians in finding cancer and predicting who will have a heart attack. These functions will seem routine in the next several years.

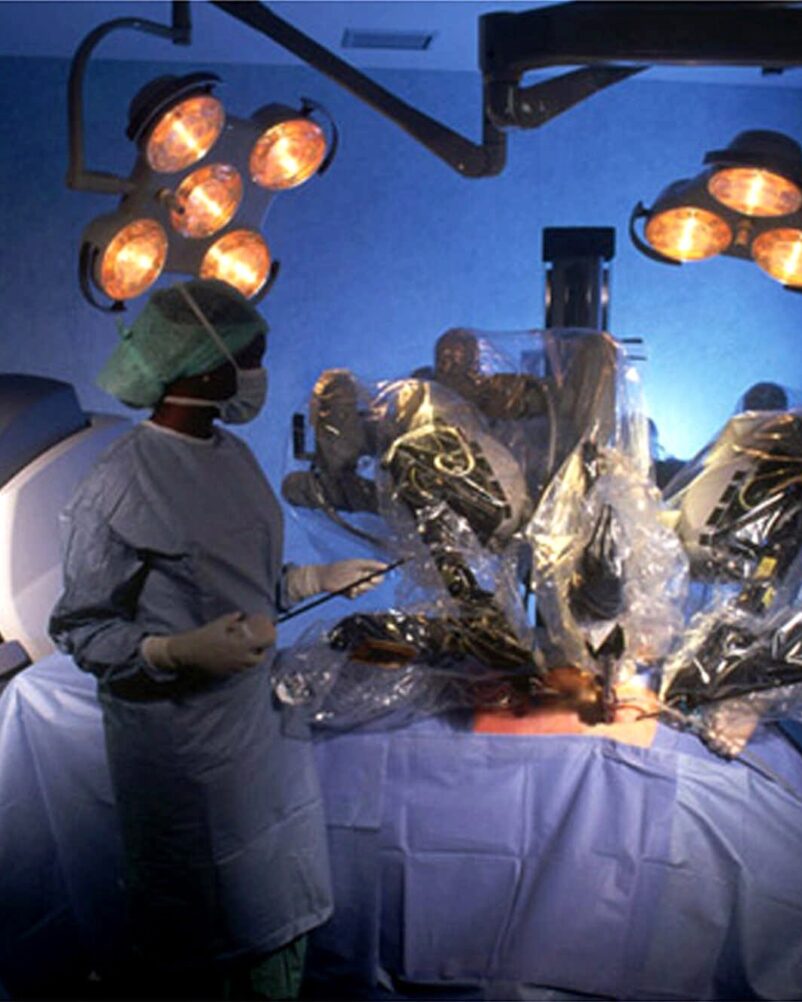

Second is surgery. You have probably heard of the current “robots” that assist surgeons. I am pointing to the next generation, where AI bots decide whether surgery is necessary and perform it without a doctor’s intervention. This concept is already underway. Recently, a cargo plane took off, and arrived at the destination gate entirely using AI — no pilots. Surgery is often far more complex than flying a cargo plane, but 25 years is a long time.

Third is bedside manner. Many physicians say that AI will never get the “soft side” of medicine with empathy and caring. Most physicians don’t know that AI empathy is on the way now. Imagine an avatar that looks exactly like a physician and then has an in-depth conversation or series of conversations with the patient and family, with highly appropriate reactions to the mood and words of the patient. Blake Lemoine, recently of Google, lost his job when he argued that his AI chatbot is already a person. A few years ago, even having that discussion — never mind the outcome of firing the engineer — would have seemed highly unlikely. In a few short years, whether an AI bot acts like a person won’t be up for discussion

What can we do? Yuval Harari in his book“Homo Deus” tells us that there is nothing we can do; we will be taken over by the software (“algorithms”). I believe he is wrong. There is plenty we can do. Two months ago, the CEO of OpenAI, Sam Altman, said to the U.S. Congress, “Regulate us” or we are essentially facing exactly what Harari predicts. Reality has met fiction. The White House was quick to react, and tech firms have been amenable to the new safeguards.

I believe that we can stay ahead of the algorithms by convening the best groups of people possible with the purpose of predicting what humans can do every five years (or more frequently) to stay ahead of the algorithms.

Let’s return to the physician. In 25 years, I believe AI is going to replace and improve on most of what “physicians” (or whatever we are called then) currently do. In any event, the changes required to educate physicians and other members of the team will be profound and will continue to change rapidly. Some physicians have projected that we will have more time to deal with the “softer side” of their patients. But again, AI will do that as well within a few years. AI is not all positive. AI can lie, and at present the way in which it works internally is not completely understood. That is a huge problem.

Educating a physician currently requires around 13 years. When our current high schoolers graduate from medical school, AI will have already created great change. It would seem reasonable to put together learned groups to project as best they can the jobs of various members of the team, and the changing educational needs of both learners and teachers. It may not be too early.

We really need to think of AI very differently.

When I was 5 years old, my father asked me, “Do you know what ‘inconceivable’ means?”

I proudly smiled, “Yes, I do! It’s like being a Martian.”

“No,” he said, “That’s conceivable.”

Arthur Garson, Jr., MD, MPH is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, a clinical professor of Health Systems and Population Health Sciences at the College of Medicine, University of Houston, and past president of the American College of Cardiology.