Hello again,

Today’s topic is … well, the same as the last one. Q Learning and Deep Q

Networks. Last time, we explained what Q Learning is and how to use the Bellman

equation to find the Q-values and as a result the optimal policy. Later, we

introduced Deep Q Networks and how instead of computing all the values of the

Q-table, we let a Deep Neural Network learn to approximate them.

Deep Q Networks take as input the state of the environment and output a Q value

for each possible action. The maximum Q value determines, which action the agent

will perform. The training of the agents uses as loss the TD Error, which is

the difference between the maximum possible value for the next state and the

current prediction of the Q-value (as the Bellman equation suggests). As a

result, we manage to approximate the Q-tables using a Neural Network.

So far so good. But of course, there are a few problems that arise. It’s just

the way scientific research is moving forward. And of course, we have come up

with some great solutions.

Moving Q-Targets

The first problem is what is called moving Q-targets. As we saw, the first

component of the TD Error (TD stands for Temporal Difference) is the Q-Target

and it is calculated as the immediate reward plus the discounted max Q-value for

the next state. When we train our agent, we update the weights accordingly to

the TD Error. But the same weights apply to both the target and the predicted

value. You see the problem?

We move the output closer to the target, but we also move the target. So, we end

up chasing the target and we get a highly oscillated training process. Wouldn’t

be great to keep the target fixed as we train the network. Well, DeepMind did

exactly that.

Instead of using one Neural Network, it uses two. Yes, you heard that right!

(like one wasn’t enough already).

One as the main Deep Q Network and a second one (called Target Network) to

update exclusively and periodically the weights of the target. This technique is

called Fixed Q-Targets. In fact, the weights are fixed for the largest part

of the training and they updated only once in a while.

class DQNAgent:

def __init__(self, state_size, action_size):

self.model = self._build_model()

self.target_model = self._build_model()

self.update_target_model()

def update_target_model(self):

self.target_model.set_weights(self.model.get_weights())

Maximization Bias

Maximization bias is the tendency of Deep Q Networks to overestimate both the

value and the action-value (Q) functions. Why does it happen? Think that if for

some reason the network overestimates a Q value for an action, that action will

be chosen as the go-to action for the next step and the same overestimated value

will be used as a target value. In other words, there is no way to evaluate if

the action with the max value is actually the best action. How to solve this?

The answer is a very interesting method and is called:

Double Deep Q Network

To address maximization bias, we use two Deep Q Networks.

-

On the one hand, the DQN is responsible for the selection of the next

action (the one with the maximum value) as always. -

On the other hand, the Target network is responsible for the evaluation

of that action.

The trick is that the target value is not automatically produced by the maximum

Q-value, but by the Target network. In other words, we call forth the Target

network to calculate the target Q value of taking that action at the next state.

And as a side effect, we also solve the moving target problem. Neat right? Two

birds with one stone. By decoupling the action selection from the target Q-value

generation, we are able to substantially reduce the overestimation, and train

faster and more reliably.

def train_model(self):

if len(self.memory) < self.train_start:

return

batch_size = min(self.batch_size, len(self.memory))

mini_batch = random.sample(self.memory, batch_size)

update_input = np.zeros((batch_size, self.state_size))

update_target = np.zeros((batch_size, self.state_size))

action, reward, done = [], [], []

for i in range(batch_size):

update_input[i] = mini_batch[i][0]

action.append(mini_batch[i][1])

reward.append(mini_batch[i][2])

update_target[i] = mini_batch[i][3]

done.append(mini_batch[i][4])

target = self.model.predict(update_input)

target_next = self.model.predict(update_target)

target_val = self.target_model.predict(update_target)

for i in range(self.batch_size):

if done[i]:

target[i][action[i]] = reward[i]

else:

a = np.argmax(target_next[i])

target[i][action[i]] = reward[i] + self.discount_factor * (target_val[i][a])

self.model.fit(update_input, target, batch_size=self.batch_size,epochs=1, verbose=0)

You think that’s it? Sorry to let you down. We are going to take this even

further. What now? Are you going to add a third Neural Network? Haha!!

Well kind of. Who’s laughing now?

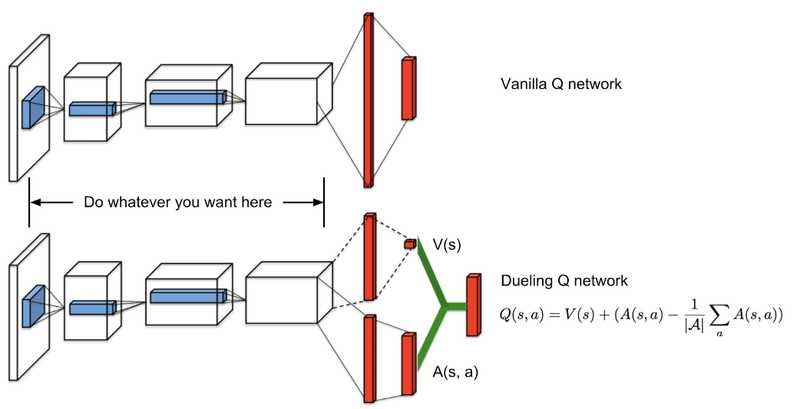

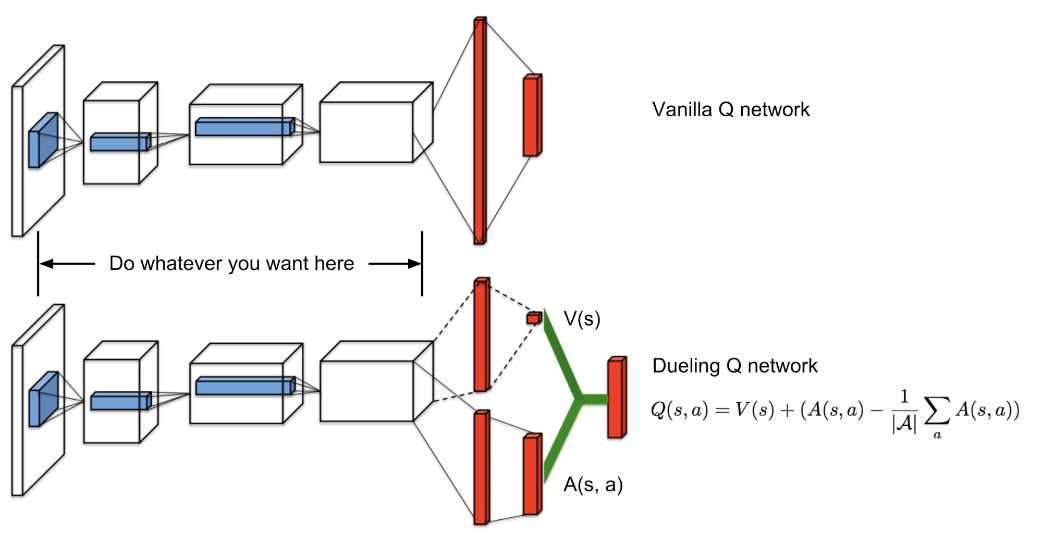

Dueling Deep Q Networks

Let’s refresh the basis of Q Learning first. Q values correspond to a metric of

how good an action is for a particular state right? That’s why it is an

action-value function. The metric is nothing more the expected return of that

action from the state. Q values can, in fact, be decomposed into two pieces: the

state Value function V(s) and the advantage value A(s, a). And yes, we just

introduce one more function:

Advantage function captures how better an action is compared to the others at a

given state, while as we know the value function captures how good it is to be

at this state. The whole idea behind Dueling Q Networks relies on the

representation of the Q function as a sum of the Value and the advantage

function. We simply have two networks to learn each part of the sum and then

we aggregate their outputs.

Dueling Network Architectures for Deep Reinforcement Learning

Do we earn something by doing that? Of course, we do. The agents in now able to

evaluate a state without caring about the effect of each action from that state.

Meaning that the features that determined whether a state is good or nor are not

necessarily the same as the features that evaluate an action. And it may not

need to care for actions at all. It is not uncommon to have actions from a state

that do not affect the environment at all. So why take them into consideration?

* Quick note: If you take a closer look at the image, you will see that to

aggregate the output of the two networks we do not simply add them. The reason

behind that is the issue of identifiability. If we have the Q, we can’t find the

V and A. So, we can’t back propagate. Instead, we choose to use the mean

advantage as a baseline (the subtracted term).

def build_model(self):

input = Input(shape=self.state_size)

shared = Conv2D(32, (8, 8), strides=(4, 4), activation='relu')(input)

shared = Conv2D(64, (4, 4), strides=(2, 2), activation='relu')(shared)

shared = Conv2D(64, (3, 3), strides=(1, 1), activation='relu')(shared)

flatten = Flatten()(shared)

advantage_fc = Dense(512, activation='relu')(flatten)

advantage = Dense(self.action_size)(advantage_fc)

advantage = Lambda(lambda a: a[:, :] - K.mean(a[:, :], keepdims=True),

output_shape=(self.action_size,))(advantage)

value_fc = Dense(512, activation='relu')(flatten)

value = Dense(1)(value_fc)

value = Lambda(lambda s: K.expand_dims(s[:, 0], -1),

output_shape=(self.action_size,))(value)

q_value = merge([value, advantage], mode='sum')

model = Model(inputs=input, outputs=q_value)

model.summary()

return model

Last but not least, we have on more issue to discuss and it has to do with

optimizing the experience replay.

Prioritized Experience Replay

Do you remember that experience replay is when we replay to the agent random

past experiences every now and then to prevent him from forgetting them? If you

don’t, now you do. But some experiences may be more significant than others. As

a result, we should prioritize them to be replayed. To do just that, instead of

sampling randomly (from a uniform distribution), we sample using a priority. As

priority we define the magnitude of the TD Error (plus some constant to avoid

zero probability for an experience to be chosen).

Central idea: The highest the error between the prediction and the target, the

more urgent is to learn about it.

And to ensure that we won’t always replay the same experience, we add some

stochasticity and we are all set. Also, for complexity’s shake we save the experiences in

a binary tree called SumTree.

from SumTree import SumTree

class PER:

e = 0.01

a = 0.6

def __init__(self, capacity):

self.tree = SumTree(capacity)

def _getPriority(self, error):

return (error + self.e) ** self.a

def add(self, error, sample):

p = self._getPriority(error)

self.tree.add(p, sample)

def sample(self, n):

batch = []

segment = self.tree.total() / n

for i in range(n):

a = segment * i

b = segment * (i + 1)

s = random.uniform(a, b)

(idx, p, data) = self.tree.get(s)

batch.append((idx, data))

return batch

def update(self, idx, error):

p = self._getPriority(error)

self.tree.update(idx, p)

That was a lot. A lot of new information, a lot of new improvements. But just

think what we can combine all of them together. And we do it.

I tried to give a summary of the most important recent efforts in the field,

backed by some intuitive thought and some math. This is why Reinforcement

Learning is so important to learn. There is so much potential and so many

capabilities for enhancements that you just can’t ignore the fact that is going

to be the big player in AI (if it already isn’t). But that’s why is so hard to

learn and to keep up with it.

If you need to dive deeper, I highly suggest the Advanced AI: Deep Reinforcement Learning Course in Python on Udemy.

Next time, we will introduce Policy Gradients and the REINFORCE algorithm

All we have to do is keep learning …

* Disclosure: Please note that some of the links above might be affiliate links, and at no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you decide to make a purchase after clicking through.