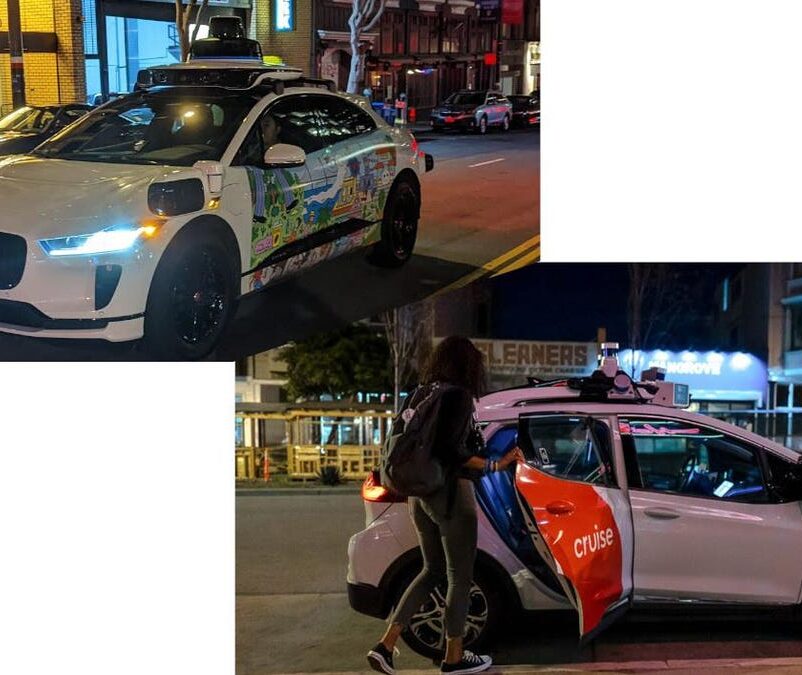

Waymo and Cruise both report over 1 million miles of no-safety-driver operation

In January, Waymo reached 1 million miles of public autonomous driving with no human monitor in the vehicle. This month, Cruise announced the same milestone. Waymo had a few years ago announced 6 million miles with safety drivers, but this is a different milestone. Cruise has fewer total miles. With their announcement, however, Waymo has published detailed safety data, including descriptions of all incidents with their vehicles which involved a contact and a number of other statistics. Cruise has declined to provide similar information, though since most of their operations are in San Francisco, many of them have been reported to the California DMV.

In other news, Waymo has also announced it has begun testing in Los Angeles with no safety driver on board, suggesting operations there may be imminent.

Waymo announced their statistics on the Waymo blog, and in a new academic paper with specific details on all their incidents.

In theory, operating with a safety driver should be similar to unmanned operation, except there is nobody to intervene and take the wheel if there is an urgent problem. Both teams have remote operators who can give the car instructions, but they can’t directly drive it nor respond by grabbing the wheel if the car is about to hit something. Safety drivers are trained to intervene any time there is anything concerning, so they often do so when the car would have resolved the matter. To test that, teams will run the situation through their simulator to find out what would have happened had nobody intervened. When it says something bad would have happened, that’s a cause for major concern. With no safety driver, that something bad always happens in that situation, and as such, the bar to operating without one is higher, and doing so for a million miles shows the confidence and internal numbers the teams have on their safety performance.

Waymo’s reported statistics are impressive. Cruise, on the other hand, has not performed as well, but worse, they decline to publish many of the statistics. As these companies (and others) move to deploy in the world, they will need to take steps to reassure the public, and not revealing the facts is a poor choice in that regard — it can’t help but raise the question of “why won’t they say?”

Waymo’s claims include:

- 18 minor and 2 major contact events in one million miles of operation

- Other vehicle at fault in all vehicle to vehicle contacts. There were 4 contacts with physical objects, 3 of which caused no known damage

- No reported injuries, no contacts at intersections, no contacts with vulnerable road users

- All events were of a class unlikely to result in a severe crash or fatality, and the serious ones were front-to-rear which only account for 19% of serious crashes and 6% of fatalities in data on the general population.

- In 55% of events, the Waymo vehicle was stopped and hit by somebody else

Waymo saw 18 minor contact events and 2 events which required a vehicle to be towed away, which means they go into NHTSA’s collision database CISS. 20 minor events in 1M miles is more than the 10 that might be expected for a human driver based on other data. However, Waymo states that all events involving another vehicle had it do something at fault, though it’s not clear if the Waymo might share some fault in a few of them. In event 3, they hit a construction cone (no damage.) In event 15 they hit a plastic sign blowing across the roadway. In event 17 they hit a parking lot barrier arm but did not damage it. In event 18 they hit a shopping cart at the exit of a parking lot.

Waymo reports no injuries in any of their operations. Sadly, Cruise can’t do the same and had at least 2 injury crashes. One, involving a left turn, had the other vehicle speed and go straight at a left turn lane, but the Cruise froze and made it worse. Details of other crashes have not been disclosed.

Crashes in California are reported in the DMV Autonomous Vehicle Collision Reports which cover unmanned vehicles, ones with safety drivers and even ones being manually driven. There are 34 Cruise reports since the start of 2022, and 71 for Waymo. To contrast their operating environments for the million miles:

- Waymo: Mostly suburban Chandler, 20-30% in downtown Phoenix and San Francisco — Cruise, almost entirely the more complex urban San Francisco environment, small amount in Chandler & Austin.

- Waymo: 20% late night — Cruise: All passenger operations are late night, but rides for staff are now done daytime.

- Waymo: Two (10%) contact events late night — Cruise: contact count and time of day not revealed

- Both companies are not driving on freeways or at high speed. City streets actually have much higher crash rates per mile than freeways, though high speeds can increase crash severity.

All of this makes it harder to compare the results of the two companies.

Cruise Chevy Bolts are now operating in the daytime for employee rides in San Francisco

Waymo’s two serious events do not appear to be their fault. In one, they were part of a group of cars stopping slowly for a red, and they were rear-ended. In another, as a light turned yellow, another car cut in front of them and then braked hard. Human driven cars have a police-reported crash about every 500,000 miles so this is in line with that number, but with blame on the other vehicles, the Waymo’s record surpasses human performance.

Waymo notes with pride that no incidents involved vulnerable road users (though one did involve a minibike whose rider had fallen off, sending the riderless minibike into the path of the Waymo) and none were at intersections, the usual location of problems.

Hitting an orange cone

While it might be strange to think this way, perhaps the most serious incident was the one with the construction pylon (presumably an orange cone.) While it’s generally harmless to hit these cones — indeed they are designed to be safe to hit because they are placed in the middle of the road and human drivers are known to hit them from time to time — this is of concern because we know that all robocars, including Waymos are on the lookout for these cones and try hard to identify them and not hit them. They don’t take less care with them because they are cones. As such, hitting a cone is a possible indicator the vehicle would hit something else it’s also trying to look for and avoid, such as a concrete bollard, which would cause great damage and be harder to see.

The impact with the barking lot barrier arm is also one of concern. While it is harder to deal with moving objects, parking lot barrier arms are expected to move and the Waymo system should be ready for that. Of course, humans also frequently hit these things. The sign being blown by the wind and the rolling shopping cart are also items you would expect humans to hit from time to time.

It’s hard to get statistics on how often human drivers hit things like these with no damage to the car or the object. This simply doesn’t get reported to anybody. I suspect most drivers have winged a cone more than once. So it’s not clear if this should be counted as an at-fault crash to compare Waymo with a human, but even if it is, as the only one in a million miles, that’s a better record than the typical human.

So, how good is it?

Waymo’s own paper on these items contains detailed analysis of how severe they think each event one, and in particular how much it bodes the risk of other severe events. By these metrics, they score well.

Waymo just started testing with no safety driver in Los Angeles and is expected to soon open … [+]

In evaluating these vehicles on the road, one of the key question is whether they are putting people at significant risk, in particular, more risk than ordinary human driving does. The goal of these projects it to take humans from behind the wheel of vehicles, and as we know, human driving creates quite a bit of risk. Waymo makes a good case that they are not creating undue risk on the roads with their pilot operations, and in fact are reducing it. Cruise does not make this case nearly as well — which is not to say that they are failing at this, but rather that they aren’t being as open on the details. Of course, none of the other companies are engaged in major uncrewed operations, or providing much data on it.

It is important that companies are proactive in disclosing this data both to reassure the public about lack of risk and to justify the much more minor traffic blockages and overly conservative road citizenship that are an expected consequence of safety policies during these pilots. We’ve seen many stories of these vehicles sometimes being honked at, or even needing rescue by a physical driver, and thus causing lane blockages. These incidents are annoying, but traffic blockage is also done very frequently by human drivers. It makes sense to tolerate it while developing these technologies as long as people are not being hurt — and these statistics are what can demonstrate where people are getting hurt. During the “safety driver onboard” phase of development, the safety record of responsible companies was generally very good, with the obvious exception of Uber and its negligent safety driver. Now Waymo is making the case that they have done the same with rider-only and uncrewed operations.

It is not entirely clear from the crash descriptions if the Waymo driver could have gone above and beyond to prevent the crash that wasn’t its fault. Waymo has in the past touted that their Waymo driver tries to do this and has succeeded many times. One of the promises of good robocars is that not only will they less frequently be the cause of crashes, but they will do extra to prevent crashes that are caused by others. Waymo used simulation of all fatal crashes in their Chandler operations area to determine that their system would have prevented most of those fatalities had it been driving the not-at-fault car. It will be good if future analysis provides details on what the system could have done better in any event. While generally, if a vehicle is hit while stopped there is less it can do, but a few of the incidents are ones where the car might have been able to proactively get out of the way.

Road Citizenship

As safety milestones are generated, the next thing that projects will be judged by will be their road citizenship. As such, we might hope to see numbers on how often vehicles are needing to pause to resolve problems or blocking traffic, in particular how often they need remote assistance or worse, a rescue driver. While these events generally are not significant safety problems, and so should be expected and tolerated to a reasonable degree in the early years, companies will soon want to show they are doing well at this.

In time, robocars will become the best road citizens, and some of the most cooperative. Research has shown that it only takes a surprisingly small percentage of well behaved cars on the road to reduce traffic problems, which is a counter to the issue that by making transportation easier and more accessible, robotaxis can increase demand for the roads.

Other operations

It’s worth repeating that this data is only for Waymo’s operations with no safety driver. As can be seen, they have had more incidents reported to the DMV in California with their safety driver operations, though this includes a fair number of manual driving incidents. Neither Waymo or Cruise have provided their own data on those incidents. More analysis will be forthcoming from that data. For now, Cruise is only disclosing what they are legally required to file with government agencies, which hopefully will improve. All companies (not just Cruise) need to go above and beyond in making the public aware and reassured about their operations. Government regulations usually don’t do the best job at mandating what’s really important for expert evaluation of performance. Of particular concern is Cruise’s official statement that their crashes have resulted in “no life-threatening injuries” which recently changed to say “no serious injuries.”