The T-shirt in the window of Baked Ts displays a technicolor Gateway Arch illuminated by city lights. Below it, “Saint Louis” is spelled out in loopy, white text.

The Delmar Loop store has a paper note affixed to the custom-printed shirt: “This design was created 100% by using an AI Graphic Design tool. Our designer specified some keywords and, after several iterations, the tool generated the design. We are always exploring leading edge solutions to benefit our customers.”

In 1985, Sam Altman, the founder of the company OpenAI that created ChatGPT, was born in St. Louis, later attending high school at John Burroughs School in Ladue. These days, his artificial intelligence creations have infiltrated nearly every field around the globe — even creeping into the art and music scene of his hometown.

AI art isn’t just digital art, or using a computer program to make designs. An AI being can “create” much like a human artist, generating images, music, video or words based off a given prompt.

People are also reading…

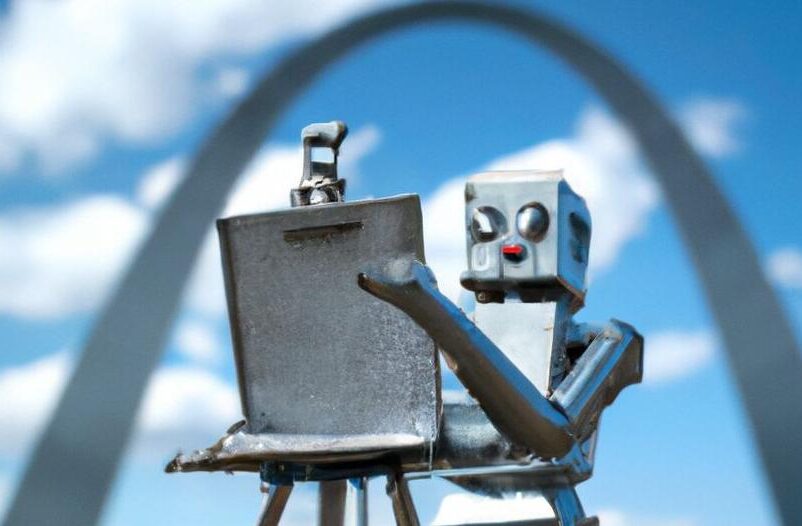

An image generated by DallE2, OpenAI’s image-generator, after multiple iterations with the phrase “robot painting St. Louis Arch.”

Artists, designers and producers in St. Louis are using, thinking or worrying about AI and how it will impact their work and livelihoods. Many say AI will play a role in how art is made and consumed here — if not already, then in the near future. Just wait.

Sam Maul, chief engineer and producer at St. Louis’ Shock City Studios, is starting to get a taste of what AI could look like. One of his clients recently created a mesmerizing AI-generated music video: It slides through a series of dreamlike patterns, moving through images of brilliantly colored instruments before panning to cartoon-like musicians, then the city, all blending into a pixelated background. Still, Maul says he doesn’t consider anything AI does to be “art.”

“For art to happen, there’s a person expressing what’s inside of them to the world and then another person receiving it,” Maul says. “So when there’s not a person on the creating end, and it’s just sort of this kind of hallucinatory — whatever that comes out of AI — to me, that’s closer to entertainment than it is to art.”

Even so, Maul sees a future in which corporations choose AI over humans when looking for stock or background music for commercials or promotions, since it’s usually cheaper to pay for AI than human labor.

“I think there’s cause for concern here because currently so many creatives in the music industry rely on creating and licensing music for these formats in order to make enough money to survive,” he says. “They’re kind of selling their skill set in the commercial market as a way to fund the artistic endeavor of making music.”

The Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts at Washington University is in the business of teaching art rather than selling it. But it, too, is diving headfirst into the vast ocean of AI. In April, the school held an “AI + Design Mini-Symposium,” inviting experts — though some had less than a year of experience — in art and AI fields to talk about future uses and integrations of intelligent technology.

Carmon Colangelo, dean of Sam Fox, introduced the symposium. He began thinking about the collision between his field (he’s a professor in art and printmaking) and AI about five years ago, when the first iterations of independently intelligent tech landed in the public eye.

“Learning about it was a little sci fi-ish. A little bit scary,” he says.

Soon after, however, Colangelo realized that AI is here to stay, and he began to organize what became the April symposium. He was expecting pushback on the idea but received little.

“There were a few emails that I got that were like ‘this is evil. We don’t want this in the school,’” Colangelo says. “But mostly I got curiosity.” Most students and professors were excited to be at the cutting edge of new technology.

Sam Fox is continuing to push ahead with AI and will be starting a search in the fall for a professor specializing in artificial intelligence and design. But Colangelo says the school isn’t abandoning the foundations of an art education.

“We still teach drawing and fundamentals. I don’t think that’s going to go away,” he says.

The Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis at the corner of Washington Boulevard and North Spring Avenue.

Several local art museums have yet to promote any exhibitions using artificial intelligence. A spokesperson for the St. Louis Art Museum says it hasn’t featured any exhibitions with AI art and has no immediate plans to do so. And the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis says it hasn’t yet worked with an artist who uses AI, and in an emailed statement wrote that members are “following the implications of artificial intelligence as it relates to art, intellectual property, and copyright laws with great interest.”

Jonathan Hanahan, an associate professor at Sam Fox, is forging ahead with AI in his artwork. In 2020 he created “Edgelands,” a digital series of photographs and videos that combined AI-generated images of Midwestern landscapes with images of illegal e-waste dumpsites in Africa, Asia and India.

Hanahan says he both “loves and is terrified” of new technology but isn’t too concerned that AI will replace human brains and creativity.

“The idea was the last thing that would be replaced would be abstract thinking and creativity,” he says. “And then actually that was the kind of first thing — but not really because it’s like it’s pretty thoughtless.”

Hanahan says the “Edgelands” project involved “tricking” AI to achieve the image he wanted by telling it two data sets were one, meaning his inputs were still the most influential aspect of the piece.

An AI-generated image from Jonathan Hanahan’s “Edgelands”

“The result isn’t interesting, unless you know what the prompt is, right?” he says.

Sam Altman agrees that creative fields like art and design are the first target of AI “thinking,” but he has a more pessimistic outlook.

In January 2022, he tweeted: “Soon, AI tools will do what only very talented humans can do today. (I expect this to go mostly in the counterintuitive order — creative fields first, cognitive labor next, and physical labor last),” he wrote. “Great for society; not always great for individual jobs.”

Nationally, the AI issue is a major factor in the current strike by SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. The union is concerned about the use of AI in generating and perpetuating actors’ likenesses.

Can the robot do my job?

John Launius will address these issues in a panel at Intersessions, part of the Music at the Intersection festival. In “A.I. in the Arts — What’s Next?” (9:15 a.m. Sept. 8, .Zack), Launius will dive into how AI can and will impact the ways St. Louis artists create.

Launius, perhaps unlike Altman, isn’t too concerned about the AI threat to individual artists. He knows some might feel threatened anyway, though history shows new technology and older traditions can co-exist.

“One of the downsides, really, is fear. Human beings are designed with a fear mechanism. But even though audiobooks now exist, well, physical books still exist.”

More pointedly, Launius says, “real” artists shouldn’t be afraid of being replaced by robots.

“If you’re an artist and you’re worried about that, are you really an artist?” he says. “I think that if you’re really engaged in the artistic process, it’s something that you’re ready to embrace, not necessarily reject.”

A sneaker painted by human artist David Ruggeri in his recent “mini-Jordan” series.

An image generated by DallE2 after the prompt “brightly colored Jordan sneaker over graffiti-style backdrop, pop art.”

David Ruggeri, a local pop-graffiti artist, is calm about the encroachment of AI into the art scene. Like Launius, he is comforted by the fact that although new technology has caused panic in the art world again and again, human artists are still abundant and well-respected.

“Artists painted portraits and landscapes so people could save those images. And then the camera came along, and you didn’t need to do that,” Ruggeri says. Rather than put artists out of work, the camera allowed new art to emerge: abstract art, interpretive art, conceptual art. He thinks AI tools will have the same effect.

Ruggeri sees himself as an active factor in the work he creates. Even though a bot might be able to produce a brightly colored Jordan sneaker over a graffiti-style backdrop (as seen in Ruggeri’s “Mini Jordans 2023 Series”), it wouldn’t be quite the same.

When he sells artwork, Ruggeri makes a point to talk to the collector and emphasize his own connection to each piece.

“I think that people who want art versus décor … I think I can add that value. Like, ‘I made it in my studio and these are the tools that I used to make it,’” he says.

Ruggeri also says AI could remove the barrier for less artistically inclined people to try something new.

“If AI brings people into the art community, if it gives them the avenue to enter the art community, then I think that’s a good thing.”

The accessibility that could come with AI is one of Altman’s main talking points when promoting his creations such as DallE, an AI image-generator.

“Artists will be much more productive and have new capabilities, but the barrier to entry will be much lower. And as the tools get better, ‘regular people’ will be able to do almost anything they want themselves,” he tweeted in early 2022.

Copyright and ownership

Xander Simms, a St. Louis extended reality (XR) and AI designer and artist, also isn’t worried about his job being taken by “robots.” In fact, he relies on the robots as part of his artistic endeavors. Simms uses Midjourney, an AI image-and-drawing generator, as a tool for his designs — mostly to make his process more efficient.

But Simms says copyright laws require that he still be the main creative force behind any protected art.

“If I’ve produced some beautiful image straight from Midjourney and don’t add some sort of human creativity to it, (a copyright office would) deem that it’s not eligible for a license,” Simms says.

Designer Mike Meyer shows off different designs he created using an art generation program called Midjourney at Baked T’s custom T-shirt store in University City. The program uses artificial intelligence to produce art based off of a text prompt given to it by a human, which can be seen above the thumbnails of the art. Photo by Michael Clubb, mclubb@post-dispatch.com

Baked Ts, the store that displays the AI-generated T-shirt, is acutely aware of the copyright laws. Dan Raskas, the president of the company, says that the shirt was made as a kind of artistic experiment when AI tools were just emerging.

“We felt that it was important for us to be aware of all the advances in technology and so we, one of our designers, took it upon himself to sign up for one of the AI services,” he says.

Raskas clarified that the design was actually “partially generated by AI,” since the designer used Adobe Illustrator and went through multiple iterations of the art to achieve the final product.

“Our biggest concern, as it pertains to AI, is to protect the copyrights and not get ourselves in a situation,” Raskas says.

Given that AI as a competent artist is a recent emergence, rules are not yet set in stone. The Art Newspaper wrote in June that “the process of publicising policies with regard to the use of AI in the arts is, to a degree, a work in progress,” explaining that current copyright regulations may change as AI technology advances.

Both Raskas and Simms say they use Adobe AI tools for simple timesaving design edits. They can use extra time and energy saved from, say, removing a photo’s background to focus on more creative processes.

Simms is working on a series of “3D AI-designed virtual sneakers that you’ll be able to wear interactively in the Metaverse experience.” Most people under age 25 could tell you that this means that the shoes can be worn by an avatar controlled by you in an interactive 3D space called the Metaverse — a concept that is grasped more easily by the youth, Simms says. He has been teaching AI courses at a St. Louis summer camp in partnership with the St. Louis Science Center. He says the kids pick it up quickly.

“Gen Alphas and the younger generations are so digitally native and internet savvy, that they really grasp the concepts and in their world, it’s just part of their identity,” Simms says.

Hanahan, whose courses at Sam Fox have included “Sculpted Realities” and “Advanced Interaction Design,” has also noticed that younger generations lean more heavily into emerging AI tech. He’s a big advocate for “breaking” the tools rather than just following the rules and found that his students were using AI in their projects in productive and exciting ways.

“I’ve been pleasantly surprised with how they’re exploring it. And not as a way to get out of work, but to actually make their work better,” he says.

Hanahan has no doubt AI will become more and more common in the teaching and learning of art at Sam Fox, a reflection of the wider art world. “It’s almost inevitable,” he says.

The meteoric rise of artificial intelligence is raising thorny questions about exactly who owns the output of AI tools. And, as AI-generated music and art crosses more into the mainstream, pressure is growing to find the answers. CNN’s Michael Holmes talks to Martin Clancy, founding chair of a global committee focused on the ethics of AI in the arts, about the promise and peril of this new technology.