TOPEKA, Kan. — Kansas could soon offer up to $5 million in grants for schools to outfit surveillance cameras with artificial intelligence systems that can spot people carrying guns. But the governor needs to approve the expenditures and the schools must meet some very specific criteria.

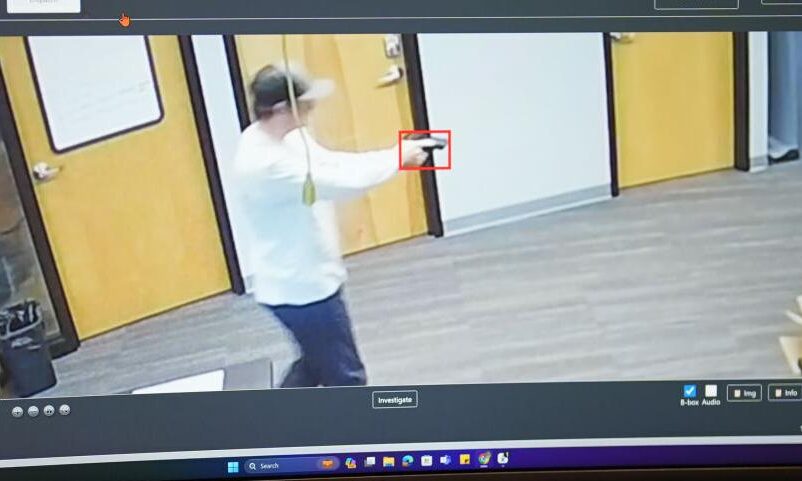

ZeroEyes analyst Mario Hernandez demonstrates the use of artificial intelligence with surveillance cameras to identify visible guns at the company’s operations center May 10 in Conshohocken, Pa.

The AI software must be patented, “designated as qualified anti-terrorism technology,” in compliance with certain security industry standards, already in use in at least 30 states and capable of detecting “three broad firearm classifications with a minimum of 300 subclassifications” and “at least 2,000 permutations,” among other things.

Only one company currently meets all those criteria: the same organization that touted them to Kansas lawmakers crafting the state budget. That company, ZeroEyes, is a rapidly growing firm founded by military veterans after the fatal shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida.

People are also reading…

ZeroEyes analyst Mario Hernandez demonstrates the use of artificial intelligence with surveillance cameras to identify visible guns at the company’s operations center May 10 in Conshohocken, Pa.

The legislation pending before Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly highlights two things. After numerous high-profile shootings, school security has become a multibillion-dollar industry. And in state capitols, some companies are successfully persuading policymakers to write their particular corporate solutions into state law.

ZeroEyes also appears to be the only firm qualified for state firearms detection programs under laws enacted last year in Michigan and Utah, bills passed earlier this year in Florida and Iowa and legislation proposed in Colorado, Louisiana and Wisconsin.

Missouri is the latest state to pass legislation geared toward ZeroEyes, offering $2.5 million in matching grants for schools to buy firearms detection software designated as “qualified anti-terrorism technology.”

Rob Huberty, chief operating officer and co-founder of ZeroEyes, talks about the use of artificial intelligence with surveillance cameras to identify visible guns at the company’s greenscreen lab May 10 in Conshohocken, Pa.

“We’re not paying legislators to write us into their bills,” ZeroEyes co-founder and Chief Revenue Officer Sam Alaimo said. But “if they’re doing that, it means I think they’re doing their homework, and they’re making sure they’re getting a vetted technology.”

ZeroEyes uses artificial intelligence with surveillance cameras to identify visible guns, then flashes an alert to an operations center staffed around the clock by former law enforcement officers and military veterans. If verified as a legitimate threat by ZeroEyes personnel, an alert is sent to school officials and local authorities.

The goal is to “get that gun before that trigger’s squeezed, or before that gun gets to the door,” Alaimo said.

Few question the technology. But some question the legislative tactics.

The super-specific Kansas bill — particularly the requirement that a company have its product in at least 30 states — is “probably the most egregious thing that I have ever read” in legislation, said Jason Stoddard, director of school safety and security for Charles County Public Schools in Maryland.

Stoddard is chairperson of the newly launched National Council of School Safety Directors, which formed to set standards for school safety officials and push back against vendors who are increasingly pitching particular products to lawmakers.

When states allot millions of dollars for certain products, it often leaves less money for other important school safety efforts, such as electronic door locks, shatter-resistant windows, communication systems and security staff, he said.

“The artificial-intelligence-driven weapons detection is absolutely wonderful,” Stoddard said. “But it’s probably not the priority that 95% of the schools in the United States need right now.”

The technology also can be costly, which is why some states are establishing grant programs. In Florida, legislation to implement ZeroEyes technology in schools in just two counties cost a total of about $929,000.

ZeroEyes is not the only company using surveillance systems with artificial intelligence to spot guns. One competitor, Omnilert, pivoted from emergency alert systems to firearms detection several years ago and offers around-the-clock monitoring centers to quickly review AI-detected guns and pass alerts onto local officials.

But Omnilert does not yet have a patent for its technology. And it has not yet been designated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security as an anti-terrorism technology under a 2002 federal law providing liability protections for companies. It has applied for both.

Though Omnilert is in hundreds of schools, its products aren’t in 30 states, said Mark Franken, Omnilert’s vice president of marketing. But he said that shouldn’t disqualify his company from state grants.

ZeroEyes analysts monitor alerts at the company’s operations center May 10 in Conshohocken, Pa.

Franken has contacted the Kansas governor’s office in hopes she will line-item veto the specific criteria, which he said “create a kind of anti-competitive environment.”

In Iowa, legislation requiring schools to install firearms detection software was amended to give companies providing the technology until July 1, 2025, to receive federal designation as an anti-terrorism technology. But Democratic state Rep. Ross Wilburn said that designation was originally intended as an incentive for companies to develop technology.

“It was not put in place to provide, promote any type of advantage to one particular company or another,” Wilburn said during House debate.

In Kansas, ZeroEyes’ chief strategy officer presented an overview of its technology in February to the House K-12 Education Budget Committee. It included a live demonstration of its AI gun detection and numerous actual surveillance photos spotting guns at schools, parking lots and transit stations. The presentation also noted authorities arrested about a dozen people last year directly as a result of ZeroEyes alerts.

Kansas state Rep. Adam Thomas, a Republican, initially proposed to specifically name ZeroEyes in the funding legislation. The final version removed the company’s name but kept the criteria that essentially limits it to ZeroEyes.

Support for holding parents accountable for their children’s crimes is growing in the US

Support for holding parents accountable for their children’s crimes is growing in the US

In separate trials earlier this year, Jennifer and James Crumbley became the first parents in U.S. history to be convicted of involuntary manslaughter for a mass shooting committed by their child.

On April 9, they were each sentenced to 10–15 years in prison, the maximum penalty for the crime. Prosecutors argued the Crumbleys ignored urgent warning signs that their son Ethan was having violent thoughts, and that the parents provided access to the gun he used to kill four classmates and injure seven other people at his school in November 2021.

According to The Marshall Project, legal observers have said that the facts of the case are unusual, yet many still wonder if it now sets a precedent for a “slippery slope,” where more parents could be criminally charged for what their children do. “I don’t have a lot of confidence in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion to pick and choose only cases like this,” Northern Illinois University law professor Evan Bernick told Al Jazeera. “Once you’ve got a hammer — and this is definitely a hammer — everything can look like a nail.”

Some worry that while the Crumbleys are white, an expansion of criminal charges against parents for the actions of their children would disproportionately affect Black parents or poor parents. That’s the concern in Tennessee, where some lawmakers recently introduced a bill that would fine parents up to $1,000 if a child commits more than one criminal offense.

At least one other recent school shooting case has also led to the novel application of criminal charges against adults. In Newport News, Virginia, prosecutors charged a former assistant principal with felony child neglect. The charges came after a grand jury report concluded that school administrators ignored four warnings from students and staff that a 6-year-old boy had a gun at school. The boy shot his teacher the same day. Like in the Crumbley case, the charge against a school administrator is believed to be the first of its kind, and prosecutors said Thursday that there could be more charges to come.

Deja Taylor, the mother of the child, was sentenced to two years for child neglect in December. The state sentence was in addition to a separate 21 months for federal crimes related to her purchase of the gun used.

The Newport News elementary school shooting was a test case for the legal question of how young is too young for a child to face criminal charges. Prosecutors have since said they will not charge the boy, but legally nothing stopped them from doing so. Last month, Virginia Gov. Glen Youngkin vetoed a bill that would have restricted prosecutors from charging children younger than 11, saying in part that it undermined public safety.

A group of former and current prosecutors chimed in on Youngkin’s decision, arguing in a USA Today opinion article that, “A child who can barely read needs treatment, not incarceration, and there are countless ways to address accountability and also get that child the necessary support to thrive and grow without involving a courtroom or prosecution.”

In Maryland, the issues of charging parents for what children do, and how young is too young for criminal prosecution, have also been roiling. There, state lawmakers passed a bill that will let prosecutors charge children as young as 10 with certain crimes. The previous limit was age 13. The move comes as some crimes spike, especially carjackings, allegedly committed by young people. It also follows a pair of high-profile mass shootings involving young people last year. But the measure also comes against the backdrop of an overall decline in youth crime in the state over the past decade.

Only a handful of children in Maryland each year are accused of the crimes in the new law, something that advocates on both sides of the legislation have pointed to, according to reporting by The Baltimore Banner’s Brenda Wintrode. Opponents of the law said it was unnecessary to address something so uncommon. Critics also generally argue that involvement with the juvenile criminal justice system may create more crime rather than prevent it. Supporters of the law said that given the small number of incidents, the legislation won’t cause a notable increase in the number of kids being pulled into the system.

Kids aren’t the only ones who could start being pulled into the system more often in Maryland. In an announcement highlighting the arrest of 20 young people accused of crimes earlier this month, Baltimore City State’s Attorney Ivan Bates made a point to mention “parental accountability,” warning: “From here on out, if you are found to be contributing to the delinquency of a minor child, my office will look to charge you and hold you accountable.”

This story was produced by The Marshall Project, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization that seeks to create and sustain a sense of national urgency about the U.S. criminal justice system, and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.

Support for holding parents accountable for their children’s crimes is growing in the US